By Clara Irazábal

Public spaces are privileged sites for the enactment and contestation of various stances on democracy and citizenship in the public sphere. Indeed, the public sphere, as the intangible realm for the expression, reproduction and recreation of a society’s culture and polity, usually encompasses divergent political visions and nurtures acute social confrontations that get played out in the more tangible public space.

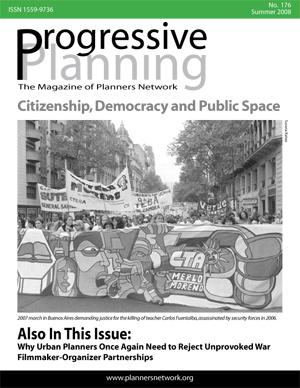

Taking to the streets is a response to issues international and domestic in nature. Alain Touraine calls it a ‘grand refuse’ in reference to the reaction of the masses in social movements to the oppressive economic conditions resultant from global neoliberalism. A ‘grand refuse,’ however, can be more than a reaction, and can catalyze a vision for alternative socio-political projects.

When oppressive conditions are challenged in unprecedented ways, social groups reconstitute citizenship by reterritorialization and appropriation of public space. New geographies of race, class, political consciousness and political affiliation can transform power, knowledge, subjectivities and ultimately, space. Significantly, the process goes both ways—transformations of space can cause transformations of power, knowledge and subjectivities.

Many studies explore the dynamics of democracy and citizenship from sociological and political science perspectives. Very few of them, however, explicitly scrutinize the development of democracy and citizenship in physical urban space, which empirically grounds these critical debates. The examination of the case studies in this issue ofProgressive Planning help interrogate the fate of the linkage between public spaces and the constructions of citizenship and democracy, critically scrutinizing the various re-workings of identity, ethnicity and other traditions of belonging. Conditions of citizenship and democracy are explored through the array of possibilities of events that can take place in public space, which range from life-making to history-making events, and all the shades in-between. Extraordinary events can unsettle the historically developed relationship between place and meaning, prompting collective re-imagining of communities and nations and thus transforming notions of citizenship and democracy.

Most demonstrations in public space do not cause radical transformations, and many of them go mostly unnoticed. But there are a few that cause reformist or radical transformations, and sometimes it is the cumulative effect of several that results in significant change. Taking to the streets, however, cannot be romanticized as a panacea for grievances and enactment of just laws and policies. On the contrary, street politics is often the last resort after all other formal procedures of claim-making for the disenfranchised prove ineffective. We do not want to be overly celebratory of street politics. Although often they have measurable impact, public demonstrations are sometimes the last resort in an ongoing struggle against inequality. Their effectiveness in ameliorating injustice varies with the leveraging power demonstrating groups have vis-à-vis power holders, the sincere commitment the latter have to issues of social justice and democracy and the actual material and non-material resources available to respond to people’s claims. Paradoxically, sometimes achieving some positive results, however partial, can void a social movement of its power and may result in the abandonment of the public space as a fruitful and dynamic arena of the political public sphere.

More than the attainment of an ideal of radical democracy, we should be interested in the radicalization of democracy. This radicalization of democracy entails different trajectories for each city and country in a context-specific search for a just city/nation. The collective imagining and mapping of such tailored trajectories in public space and all other open venues of the public sphere, and the actual traversing of those paths, are what can ultimately help achieve the best conditions possible for full citizenship. In this venture, public space can be both a springboard for mobilization and an indicator of the sincere commitment to democracy on the part of the ones that create, maintain, regulate and use these spaces.

As phoenixes, some new regimes of democracy and citizenship seem to be regenerating or arising anew from the ashes and through fire: youthful, vital and colorful, with a sense of mission and their pains and joys, their blood and sweat pulsating in their urban public spaces. People participating in a myriad of extraordinary events give shape to these new regimes of democracy and citizenship, figuratively exclaiming in unison“¡SI SE PUEDE!”—Yes we can!

The essays in this issue reassert the vitality and vibrancy of public space politics in a world that is experiencing a significant decrease in opportunities for expression in public space. These examples can help us envision a progressive politics that translates into planning theory, education and practice grounded in a sophisticated understanding of citizenship and a challenge to neoliberal urbanism. This should invite planners and policymakers to critically problematize their roles so as to effectively mobilize, give room and acknowledge the types of citizenship practices that empower individuals and societies.

[These comments and the contributions contained herein related to Lima, Mexico City, São Paulo and Buenos Aires build on the book Ordinary Places, Extraordinary Events: Citizenship, Democracy and Public Space in Latin America (ed., Clara Irazábal. Routledge, 2008).]

Clara Irazábal is an assistant professor of international planning at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University.