By Jackie Leavitt, Tony Roshan Samara and Marnie Brady

In 2007, grassroots organizers in the United States formed the U.S. Right to the City (RTTC) Alliance as a means of taking their cities back from the coalitions of affluence that had formed during the 1980s and reframing the central scale of social struggle from the global to the urban. RTTC is one of the first mass formations to emerge from the previous era of sustained anti-globalization struggle stretching from the end of the Cold War through the election of George Bush, the attacks of 9/11 and the war on Iraq. Although it is a relatively new movement, RTTC holds much potential for re-centering and advancing the struggle for democratic urban governance. Planners Network has joined RTTC as a resource group.

RTTC developed out of dialogue and organizing between the Miami Workers Center, Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (Los Angeles) and Tenants and Workers United (Alexandria, VA). Today the alliance is composed of over forty core and allied members spanning seven states, nine major cities and eight metro regions: Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, New York, Providence, San Francisco/Oakland and Washington D.C. Since 2007, the alliance has developed a national governance structure, regional networks and thematic working groups that collaborate with allied researchers, lawyers, academics, movement strategists and funders. In its own words, Right to the City “is a national alliance of membership-based organizations and allies organizing to build a united response to gentrification and displacement in our cities. Our goal is to build a national urban movement for housing, education, health, racial justice and democracy. We are building our power through strengthening local organizing; cross-regional collaboration; developing a national platform; and supporting community reclamation in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast.”

In RTTC’s first two years, the volunteer steering committee has hired two staff people and organizational development consultants. A representative from each region is on the steering committee and there is staggered replacement of members. Annual national meetings consist of workshops for members of participating organizations, subcommittee meetings, formal and informal networking activities and debate of organizational objectives, i.e., a campaign in which all members agree to participate. Other national events have included gatherings in Miami, Florida, and Providence, Rhode Island, both planned to take advantage of the U.S. Conference of Mayors meeting in these cities and for the Right to the City-U.S. to issue its own demands and support the regional alliances’ ongoing work. Critically, these meetings help regional and local groups press their campaigns as well. In late September of this year, the steering committee, staff and representatives from each region met in order to discuss the visions, goals and objectives of RTTC as an organization. The meeting of twenty people was modeled in such a way that everyone had a voice and time to reflect, learn to trust each other and reach consensus. Such a process is important to sustain as RTTC grows to ensure that it adheres to its ideals of creating a genuinely more democratic form of democracy.

The “right to the city” as a concept has captured the imagination of many involved with urban social struggles but it remains an underdeveloped social movement ideology. Below we provide an introduction to the alliance by briefly discussing some of the campaigns in which members in the Boston and New York City regions are engaged. We then attempt to draw out some of the key principles and issues which underpin these efforts and inform initiatives to develop national expressions and link these groups to others across the country and globe. Our data are drawn from interviews with RTTC members, participant observation and review of movement documents and campaigns.

The City as Battleground

What unites the various RTTC members can be traced to the conditions facing urban communities across the country. Recent decades have seen once abandoned or neglected central cities reemerge as central economic and political nodes in the global economy; as a result, struggles over urban space have intensified. Although member organizations were formed in response to highly specific local events, their struggles are defined by the need to defend urban neighborhoods from encroaching developers and gentrifiers, to confront apathetic, negligent or antagonistic officials and to grapple with the local, national and global forces that govern urban spaces in their interests. In doing so, RTTC organizations, as well as the broader communities from which they come, are engaged in an attempt to radically redefine and reclaim urban democracy. They are guided by a deeply held belief that they have a right to the spaces they call home.

City Life/Vida Urbana, based in the Jamaica Plains neighborhood of Boston, was founded in 1973 to fight disinvestment and over time it has expanded its tenant organizing to other parts of Boston. It pioneered the idea of an “Eviction Free Zone” and a “Community-Controlled Housing Zone” to resist evictions, make visible existing ownership patterns and identify where power was situated (see article in PN, pp. ). Other RTTC organizations were founded in response to more recent neoliberal policies, such as that established by the Los Angeles City Council when it approved “workforce” housing on an ad hoc basis but avoided investing major resources into housing for those of the lowest income. L.A. has exacerbated conditions for the poor by pursuing “glamorous” projects like entertainment complexes that ultimately demolished buildings, displaced tenants and reduced the housing supply for those most in need. In response, RTTC-LA has begun a campaign to develop a community-based housing plan. This involves tenant leaders surveying neighbors to document code enforcement violations based on their lived experiences; in the process, new leaders are emerging and survey findings are expanding the ways in which regulating code enforcement is tied to larger questions about power and the community.

New York City’s Right to the City regional formation emerged in 2007 from an existing coalition of anti-gentrification community-based organizing groups. The chapter’s membership-based groups are working on individual and interconnected campaigns, all of which share a strong focus on leadership development of their respective and collective membership base. For example, Fabulous Independent Educated Radicals for Community Empowerment (FIERCE), an LGBTQ youth of color member-group, is organizing for the right to public space by opposing the privatization of NYC’s waterfront and campaigning for a youth-led community center on Pier 40 in the West Village. FIERCE has played a key role in organizing youth-led forums to promote and support youth leadership in RTTC at both the local and national levels.

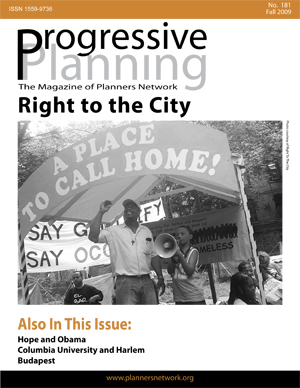

Picture the Homeless is another one of RTTC-NYC’s nearly twenty base-building groups. It was founded by homeless people in 1999 in the midst of New York City’s war on poor and working-class people of color. Seeking justice and respect, the organization is led by the homeless and intent on stopping the criminalization of homeless people. It organized a series of direct actions in 2009, including the occupation of a vacant building and the orchestration of a tent city on a vacant land parcel in East Harlem owned by JP Morgan Chase—a firm that received billions of dollars in public TARP funding. The organization’s “Housing, Not Warehousing” campaign calls for the conversion of vacant buildings to affordable housing for homeless and low-income NYC residents.

This year, RTTC-NYC issued a platform related to the upcoming citywide elections. Through a participatory and unifying process involving member organizations and allies, the local alliance identified key issue areas: federal stimulus funds; community decision-making power; low-income housing; environmental justice & public health; jobs & workforce development; public space. The platform document not only articulates key policy opportunities, it also lays out an historical and political analysis questioning the commodification of basic human needs such as housing. The platform also grounds policy concerns within a set of principles for each issue area and maps out public space accessibility, stimulus funding sources, environmental health indicators and poverty statistics for the city.

Linking Theory and Practice

As a movement and a theory, right to the city remains a work in progress. Within and beyond the RTTC, individuals and organizations are involved in the difficult political work of generating a theory that is both rooted in both the day-to-day struggles and realities of people’s lives and capable of creating opportunities for radical, long-lasting, social change. While the debate will continue, looking at RTTC campaigns allows us to begin to identify some emergent principles.

Right to the city at its most elementary concerns the relationship between people and place. It is from here, arguably, that all other rights are derived from and, in turn, grounded in. Drawing from Henri Lefebvre’s original work from 1968, Le Droit a La Ville (Right to the City), right to the city is a political feature of the urban inhabitant, a new form of political belonging not rooted in national citizenship but in urban residency, from which it draws its political power. Issues related to residency have surfaced recently in immigrant struggles to get the vote in local and municipal elections and there is a history of undocumented immigrants gaining voting rights in school elections.

From this central principle, we can see in the actions and analyses of RTTC members and the alliance as a whole a subset of rights that gives a more defined form to the rights to the city. These are neither written in stone nor apply universally to all communities in all places, but they do allow us to move the process of defining the right to the city forward as grounded in actual struggle. Engagement with an ever-widening circle of social movements committed to deep transformation will only strengthen the frame.

RTTC offers planners an opportunity to use their research skills in ways that support social movements. Campaigns about evictions, gentrification, public space and community and neighborhood planning can make use of planning in creative and innovative ways. Ava Bromberg, a UCLA doctoral student in urban planning, and Nicholas Brown, a doctoral student in landscape studies at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, assembled an exhibition and symposium series at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) in the fall of 2007. The work addressed spatial injustices and efforts to make just spaces. The entryway of the exhibition was framed by RTTC principles of unity and projects addressed economic and environmental justice practices, spatial segregation, prisons, borders and indigenous land claims. RTTC-LA held a meeting in the exhibition space, which was intended to be useful to organizers and to bring together geography-informed approaches.

Bromberg also put together a mobile planning lab for South Los Angeles, a project stemming from the exhibit contribution of four Baltimore-based artists who developed drawings. The lab is being activated in conjunction with a grassroots community planning and research project in the neighborhoods surrounding the University of Southern California (USC) being affected by USC’s expansion and the rapid transformation of affordable family housing to unaffordable student housing. The lab is modeling a community engagement and empowerment process for land use planning that can be implemented by other groups.

Planning students from UCLA and USC have served as scribes and translators for conferences on topics that help RTTC and member organizations. A two-quarter class at UCLA on Right to the City was offered where community organizers worked with students to explore the ways that the principles could further organizing in gentrified and gentrifying neighborhoods.

Planners should keep in mind the following principles that can guide their work:

The right to participate. Within the context of a right to stay, perhaps the most important right is the right to participate in all levels of decision-making, including planning regarding the community. Right to the city is deeply implicated in the struggle over how cities will be governed and by whom. Scholars across a range of disciplines have begun to study changing notions of citizenship resulting from transnational migrations, a rescaling of politics and the work of social movements and activists. While national citizenship remains the central frame for membership in a formal political community and rights’ claims, this dominance is being challenged by developments on the ground. As a result, we have an opportunity to redraw existing political maps and create new forms of citizenship and new scales of governance through social struggle. This opportunity is central to right to the city, as movement and theory. In this frame, democratic rights, rather than being based on formal political membership in a national community, are based on physical presence in the city and participation in its economic, social and political life.

The right to security. Insecurity marks the lives of many people living in urban areas across the world. Being present in a place and having a right to participate are only meaningful if people are secure. Human security refers to the full spectrum of security, addressing issues ranging from sexual assault and lack of food to armed conflict and environmental destruction. At the level of the city, human security issues are apparent in the terror sown by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids and racial profiling by police to the instability resulting from electricity cutoffs and evictions. The right to security, though its content will have to be determined by communities themselves, asserts that in principle people have the right to demand urban policies and practices which support, rather than undermine, the security of people.

The right to resist. Faced with the real threat of community breakdown and displacement—whether by gentrification, foreclosure, systematic discrimination from immigration or criminal justice authorities, malign neglect or any of the other myriad ways in which communities are broken—right to the city means a right to resist. Resistance here has to mean more than permitted marches and other overregulated forms of “free speech” like public hearings. It is a right that can be claimed by people marginalized from formal political processes, or for whom these processes have proven to be ineffective or, at times, weapons of the powerful. It is a right that questions the fundamental legality and morality of existing institutions and practices, and therefore takes as its primary goal their reform or abolition.

Linking Rights, Democracy and Planning

It is impossible to disentangle the discussion of rights from that of democracy, and perhaps right to the city is best understood as one of this generation’s attempts to breathe new life into government by the people, as the struggle for radical democracy and what some call deep democracy. At the same time, the movement and theory must be grounded in the lives of real people and the concrete conditions of urban communities. Categories such as citizen and worker, while still relevant, are insufficient to contain and represent the multi-faceted struggles of urban inhabitants who are women, documented and undocumented immigrants, LGBTQ and people of color, many of whom may exist at the peripheries or even outside of the formal economy. New struggles for democracy, inside the city and beyond, will need to create political subjects and agendas that transcend these categories without losing sight of the particularities that shape their lives of urban inhabitants.

Central to RTTC campaigns and analyses is the idea that the struggle for democracy today requires a return to the concept of rights. Students may study ethics in some programs, but planners need to ask how prevalent this is in most planning programs and practice. What would planning look like if classes and practice began from the frame of rights? Along with academic, policy and other movement allies, RTTC is engaged in the process of revitalizing the rights struggle and re-raising unsettled questions in the context of new political challenges. Questions of inclusion, for example, are far from new, yet the attack on immigrant communities forces us to acknowledge that we still lack a powerful rights movement and institutions that can adequately protect them. Similarly, market-driven displacement, criminalization and unresponsive elected officials reveal the inability of even citizenship to safeguard peoples’ civil rights. Finally, existing rights, those guaranteed to citizens and for which many documented and undocumented immigrants strive, fail to even address basic issues of human security, including housing, medical care and employment. In all these instances, communities are once again coming up against the limits of the individualistic and formal political rights that mark the liberal democracies.

RTTC and other movements like it across the globe have their work cut out for them. But there are encouraging signs of momentum. In addition to ongoing regional and national work within the alliance, RTTC recently co-convened the Inter-Alliance Dialogue, a process of discussion and joint activity between Grassroots Global Justice, Jobs with Justice, National Day Laborer Organizing Network, National Domestic Workers Alliance and RTTC. Beyond the U.S. border, the 2010 World Urban Forum V, to be held this coming March in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, has taken as its theme Right to the City. This is certainly encouraging. While much remains to be done, much has also been accomplished. Planners should seize the moment.

Jackie Leavitt (jleavitt(at)ucla(dot)edu) is a professor of urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles. Tony Roshan Samara (tsamara(at)gmu(dot)edu) is an assistant professor of sociology at George Mason University. Marnie Brady (mbrady1(at)gc(dot)cuny(dot)edu) is a Ph.D. student in sociology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. The authors each work with the Right to the City Alliance as resources allies.