By María-Teresa Vázquez-Castillo

This is our land. This is our street. Get the hell out of here.

–Joseph Turner, founder of Save our State (SOS)

In the early twenty-first century, a new stage of the anti-immigrant city is in the making, targeting immigrant communities of Latino origin, specifically of Mexican origin. Between 2005 and 2007, California cities such as Escondido, Costa Mesa and Newport have used city planning tools to control immigration within city boundaries based on arguments about securing the border and protecting the fiscal well-being of urban areas. In response, cities such as Los Angeles, Maywood and San Francisco have proclaimed themselves sanctuary cities, safe for immigrants.

Background

California cities are not the only ones drafting and approving ordinances to control immigration. More than fifty cities, suburbs and towns of all sizes and populations have followed these trends. Even areas with insignificant increases in immigrant populations are launching anti-immigrant ordinances as “pre-emptive” measures to prevent the relocation of immigrant communities within their jurisdictions or to expel the immigrants already present. This is the case of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, which on 13 July 2006 approved three anti-immigrant ordinances: the Illegal Immigration Relief Act Ordinance, the Landlord-Tenant Registration Ordinance and the Official Language Ordinance. These ordinances restrict the hiring of undocumented labor, ban landlords from renting to the undocumented and make English the official language (see “Controlling Immigrants by Controlling Space” in this issue).

Like Hazleton, the City of Escondido, California, claiming that immigrants cause overcrowding, crime, poverty and disease, approved several anti-immigrant ordinances. One of the Escondido ordinances bans renting to undocumented immigrants by requiring landlords to check a tenant’s immigration status and report it to the city. In turn, the city must check the tenant’s status with the federal government. If tenants are found to be undocumented, landlords have ten days to evict or else face “misdemeanor charges, fines and the loss of their business license.” Other ordinances ban undocumented residents from jobs, education and medical attention, while still others prohibit “overcrowding,” change the definition of “family” in zoning codes and declare their cities as English-only territories.

Exclusionary Zoning and Anti-Immigrant Planning

It is well-known that zoning regulations and ordinances have been used historically to exclude and segregate so-called minority populations. The history of the development of urban and suburban areas is full of examples of exclusionary practices against African Americans, Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese and Jews, among other groups. Although the civil rights movement attempted to eliminate these discriminatory practices, they have endured, disguised in new forms. Traditionally, prejudiced city officials, administrators and planners have used planning tools to legitimize segregation in or deprivation of access to housing, transportation, recreational activities, education and other services.

The proposal and passage of anti-immigrant ordinances have divided residents of these cities, creating tension between different ethnic and religious groups, different generations of immigrants, the business and landlord communities and civil rights organizations. This last sector has challenged the legality of the ordinances with regard to the violation of fair housing laws, contract rights and due process. Between October 2006 and September 2008, some of the anti-immigrant ordinances have been defeated, but because new ones are on the way, it is crucial to understand the dynamics and forces supporting them. Paradoxically, the regulation of international immigration has moved to the local level as cities and towns make decisions about immigration, something traditionally only done by the federal government. And though countries in the European Union are competing to showcase themselves as examples of diversity—highlighting their multicultural assets and their success in integrating immigrants into city politics to promote local economic development—the U.S. in the wake of 9/11 has lurched in the opposite direction.

Costa Mesa and Maywood

Two Southern California cities, Costa Mesa and Maywood, are prime examples of contradictory stances on immigration. While Costa Mesa has proposed anti-immigrant ordinances, Maywood has become a sanctuary city. Costa Mesa is located in Orange County, just over forty miles from downtown Los Angeles, and has a population that is nearly one-third Latino. Maywood, located just under ten miles from downtown Los Angeles, has a population that is 97 percent Latino. Interestingly, both cities have been losing population since 2003. It is important to highlight this trend because population growth has often been an argument used to justify hostility toward immigrants. While anti-immigrant Costa Mesa is an affluent beach community, immigrant-friendly Maywood is a working-class city. Thus, not only ethnicity, but social and economic class, are important elements in determining the friendliness of cities towards a low-income immigrant population.

The National Context

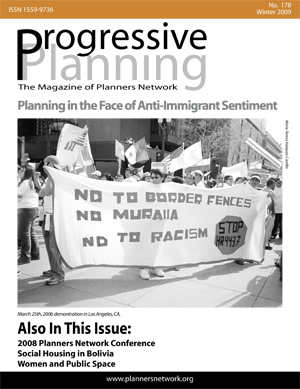

At the national level, the atmosphere toward immigrants has been poisoned by stepped-up immigration raids and adoption by the House (but not the Senate) of the Border Protection, Anti-Terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005, otherwise known as the Sensenbrenner Act or H.R. 4437. The name of the act demagogically blends border protection with anti-terrorism. By portraying Mexicans as the “illegals,” the act has contributed toward racializing the word immigrant to signify Latinos in general and Mexicans in particular. As part of the same trend, hate crimes against Mexicans have increased.

In this context, municipal policies directed against immigrants are part of a national anti-immigrant backlash. Imprisoning undocumented workers, denying them the right to a hearing and penalizing the provision of humanitarian aid to them, as proposed in the Sensenbrenner Act, all violate international human rights. When cities enter the picture and begin denying the right to mobility and the right to housing, they are challenging their residents’ basic civil rights.

Costa Mesa: Anti-immigrant City

Costa Mesa was the first city in the country to actually approve funding (about $195,000) to train members of its local police to act as immigration officers. As part of this anti-immigrant agenda, that same year, Costa Mesa’s city council voted to close the Costa Mesa Job Center, a day labor site, in order to prevent the hiring of undocumented workers. Despite a population that was 29 percent Latino and in which 24 percent of residents had Mexican heritage, the city council had no Latino representation at the time these anti-immigrant measures were approved. With five council members, all Anglo and anti-immigrant, the City of Costa Mesa voted to support HR 4437 in March of 2006. The Costa Mesa regulations violated the civil right of access to housing and the international human right of access to health, education and humanitarian aid. For the city council and its supporters, it did not matter that the city had gained a reputation as an uncompassionate, xenophobic city.

Maywood: “Sanctuary” City

In 2005, the city of Maywood, like many other cities in the region, implemented checkpoints supposedly to make sure that drivers had a driver’s license. As a result, the cars of the many unlicensed drivers, mostly working-class Latinos, were impounded for a month, causing a huge economic hardship in a city in which the median household income is less than $37,000. In addition to the impounding of their cars, drivers were also penalized with fines. In response, the city council, composed of five members of Latino origin, decided on a radical measure: eliminating the traffic division within the police department. This predominantly Latino and working-class city also became the first city to pass a resolution to oppose the Sensenbrenner Act, in January 2006. Then in April 2006, Maywood declared itself a sanctuary city. Since 2006, other cities have followed Maywood’s example by declaring themselves sanctuary cities. One city to follow suit was San Francisco, where Supervisor Tom Ammiano declared: “When certain people are targeted and denied access to social services, the health and safety of the entire city is compromised.”

Rejecting the adoption of immigration functions at the local level has levied a high price. Anti-immigrant groups such as the Minuteman and Save Our State (SOS) have been targeting the sanctuary cities, protesting outside city halls and lobbying for a reduction in the federal funds granted to sanctuary cities. In Maywood, Mayor Thomas Martin began receiving death threats and hate mail. The situation has become so hostile that in a phone interview in October 2007, a Maywood municipal staffperson urged me to avoid the use of the word “sanctuary” to refer to the city as it was “very problematic.” Anti-immigrant attacks are undermining Maywood’s public stance as an inclusionary and integrationist city.

“Repentance” Cities

Most recently, a third model of city has emerged: the Repentance City. An example of this type of city is Riverside, New Jersey, which, after passing Sensenbrenner-style ordinances and regulations, reversed its decision when it witnessed the flight of Latinos (mostly of Brazilian origin). Recently, one of Riverside’s civic and business leaders has been touring East Coast cities, giving inspirational talks and advising other cities: “Don’t do what we did. It will drag the reputation of your town into the mud.”

Two Models and the Beginning of a Third

The cases of Costa Mesa and Maywood point to two models of cities that are emerging within the new immigration regime in the United States. On the one hand, we have the anti-immigrant city, characterized by a highly organized community that opposes not simply Latino immigrants, but specifically Mexican immigrants. On the other hand, we have the re-emergence of the sanctuary cities. The sanctuary city is a form of resistance that claims a right to space and a right to the city. Unfortunately, sanctuary city policies are typically characterized by slow response, poor organization and low funding. These cities are under attack by anti-immigrant forces that, in their quest to resist the browning of U.S. cities, mobilize an abundance of financial, media and political resource and manage to resist feeling any shame about supporting policies that violate international human rights and local civil rights.

These two models of cities point to divergent directions in community organizing. Anti-immigrant cities rely on racist community organizing, where groups like the Minutemen and SOS organize their constituencies to undermine the incorporation and integration of immigrants, ignoring the destructive consequences for the local and state economy. Sanctuary cities follow a humanitarian and cross-border community organizing tradition, acknowledging the advantages of capitalizing on the diversity of immigrant communities.

Perhaps most interesting of all is the recent emergence of repentance cities, which hold the promise of overcoming anti-immigrant politics and gaining new allies for immigrant rights.

Maria Teresa Vázquez-Castillo is an assistant professor in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at California State University, Northridge.