By Nikhil Aziz

Water and other natural resources are at the center of conflicts worldwide, in large part due to their unequal distribution. These conflicts are both paradigmatic and traditional, involving a fundamental difference over whether water is a human right or a marketable commodity.

For rural small producers from the Middle East to Latin America, there is no question that access to and control of water is essential to their very survival. The source of the water challenges these producers face vary across the globe, from occupying powers to a state of war, and from government-sponsored, top-down development models to corporate interests that promote private gain over public good. When viewed through the lens of resource rights, globalization is shrinking the global commons through the concentration and privatization of natural resources. Social change movements of small producers are at the forefront of envisioning and realizing more sustainable alternatives.

Water Wars

Indian author, scientist and activist Vandana Shiva, a member of the Resource Rights Advisory Council of Grassroots International (GRI), a human rights and international development organization, writes in Water Wars: Privatization, Pollution and Profit that the wars now being fought over water are both paradigmatic and actual. In the first instance, the dispute is over how we see water—as a natural resource and public good that is enshrined in international conventions and laws as a basic human right, or as a commodity that is privately owned, traded and marketed for profit by corporations to those who can afford to purchase it.

GRI has launched a three-year Resource Rights Initiative combining grantmaking in the Global South with education and advocacy in the United States to address these issues. Our partners, social change movements and organizations engaged in the struggle for resource rights, are in the cross fire of both kinds of wars. Many of them are rural organizations of small producers, including the peasants, fishers, landless workers and indigenous peoples that constitute the majority of the world’s population. Water, and access to and control of it for agriculture, is a fundamental human right essential for these producer’s very survival—whether they are in Pernambuco, Brazil, Chiapas, Mexico or the West Bank, Palestine.

While these conflicts are not limited by geography, neoliberal globalization, as manifest in free trade treaties like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) or multilateral institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO), has only exacerbated their intensity and impact around the world. The United Nations estimates that over a billion people do not have adequate access to water. At the same time, 70 percent of the world’s water usage goes towards large-scale, heavily subsidized, export-oriented agricultural production. The model of agriculture, water use and privatization of resources promoted through NAFTA and the WTO enables food dumping and increases costs for basic services such as water delivery.

Watering Down Ethnic Conflict

Many in the United States see the Palestine-Israel conflict as a clash of civilizations, an unending battle between Muslims and Jews or Israelis and Arabs. GRI and our Palestinian partners, such as the Palestinian Agricultural Relief Committees (PARC), recognize it at its very core to be a conflict over land and water, arising out of the unjust control and distribution of these resources. Existing in many parts of the world, such conflicts often have more to do with access to or ownership and control of scarce or unequal resources rather than with the particular religion, language or ethnicity of the opponents.

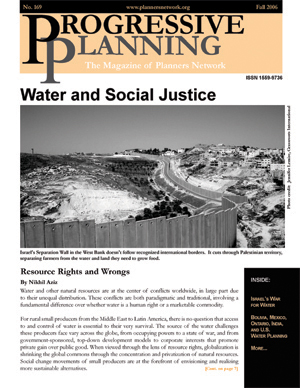

Since its 1967 occupation of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, Israel has controlled Palestinian water through its military and its national water authority, Mekorot. Vandana Shiva notes that Israel consumes over 80 percent of the West Bank’s water, which amounts to between 25 to 40 percent of Israel’s water consumption. In a land-scarce and water-stressed climate, lack of access to or control of both resources is extremely devastating to the survival of Palestinians as a people.

At a micro level, Israeli control of Palestinian water includes determining if, when and how much water individual Palestinian farmers (the majority of Palestine’s population is rural) can use for growing their crops; whether and how deep they are permitted to dig wells on their own lands (while illegal Israeli settlers can build swimming pools); or whether they can repair water infrastructure that is destroyed by the Israeli military. At a macro level, controlling water access is the foundational building block of Israel’s unilateral redrawing of boundaries through its separation wall in the West Bank, effectively annexing not just land but also water by blocking Palestinian access to the Jordan valley and various underground aquifers. Both the continuing occupation and the wall are a violation of Palestinian human rights and illegal under international law.

The Palestinian Hydrology Group (PHG), a member of the Stop the Wall Campaign, a GRI partner, monitors and disseminates information on the impact of Israel’s occupation and annexation of the Palestinian Territories’ resources, such as water, on Palestinian civil society. PARC, the PHG and other organizations like the Union of Agricultural Work Committees and the Land Research Center also work with Palestinian farmers to ensure their access to and control of water by creating, maintaining and rebuilding their water infrastructure. For them, their work is a means of resisting the occupation and is part of the struggle for liberation in the form of Palestinian statehood within the 1967 borders.

Water under the Bridge: Big Business and Big Government

Resource rights violations are not limited to occupying powers or to disputes between nations or between states and provinces within countries. Multinational corporations and governments pursuing neoliberal economic policies and top-down development models are regular violators of these fundamental human rights as well. War on Want’s Coca-Cola: The Alternative Report documents one such example of a multinational that, in its quest for profit, is at the front and center of the water wars in many parts of the Global South.

The report cites an article written by GRI grantee Centro de Investigaciones Económicas y Políticas Acción Comunitaria (CIEPAC, or the Center for Economic and Political Research and Community Action). This article, “La Coca-Cola en M é xico: El Agua Tiembla,” draws attention to the soft drink giant’s pressuring of local government officials in Mexico’s Chiapas state to use zoning laws in its favor and allow for the privatization of communal or state-owned water resources, even as indigenous peoples and campesinocommunities are frequently denied access to water. Chiapas, where CIEPAC is based, has Mexico’s largest rivers, but according to Counterpunch columnist John Ross, 68 percent of its 1.3 million indigenous people do not have safe drinking water. Furthermore, while almost 25 percent of Mexico’s water is located on or under indigenous lands, many indigenous communities do not have access to it.

The World Commission on Dams report issued in 2000, Dams and Development: A

New Framework for Decision-Making, suggests that at least 40 to 80 million people have been displaced globally by mega water projects, including large dams and reservoirs, hydroelectric power plants, flood control schemes and irrigation canals. The overwhelming majority of those forcibly displaced have not been adequately resettled, rehabilitated or compensated. Governments (both Global South and western), international financial institutions (like the World Bank) and multinational corporations (including agribusiness, mining, power and construction companies) are firmly joined at the hip in pursuing these mega projects implemented in the name of the very people they displace, and whose rights they violate or deny.

GRI partner Pólo Sindical dos Trabalhadores Rurais do Submédio São Francisco (Union Pole of Rural Workers of the Lower-Middle São Francisco River Valley ) works with displaced rural communities along the border of Brazil’s Pernambuco and Bahia states. It formed in 1979 in response to the displacement of 40,000 to 70,000 Brazilian peasants by the Itaparica Dam. A lead player in Brazil’s Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens (MAB, or Movement of Dam Affected Peoples), Pólo has taken up the struggle against the proposed redirection of the São Francisco River. Touted by Brazil’s federal government as a magic bullet that would irrigate the semi-arid northeast, provide drinking water and benefit 18 million people, the project, like many others of its kind around the world, will more likely displace people in the tens of thousands, benefit a few industries and agribusinesses and further degrade an already heavily damaged ecosystem.

Food Sovereignty and the Right to Water

Shiva disagrees with some analysts who claim that in the future conflicts over water will replace current ones over oil. She argues that water wars are taking place now and, in fact, have been going on for some time. Resistance, including posing sustainable alternatives to the dominant paradigm, has been part and parcel of the strategies of social justice movements around the globe. Peasant organizations are working with indigenous groups, women’s movements and environmental justice activists on multiple fronts, from the very local to the national and international levels. For example, movements like La Via Campesina, a global network of hundreds of organizations representing 150 to 200 million small farmers, farmworkers, fishers and foresters, are promoting “food sovereignty” and demanding equitable access to land, water and other resources within a universal human rights framework. For the Via Campesina :

Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to define their own food and agriculture; to protect and regulate domestic agricultural production and trade in order to achieve sustainable development objectives; to determine the extent to which they want to be self-reliant; to restrict the dumping of products in their markets; and to provide local fisheries-based communities the priority in managing the use of and the rights to aquatic resources. Food sovereignty does not negate trade, but rather, it promotes the formulation of trade policies and practices that serve the rights of peoples to safe, healthy and ecologically sustainable production.

Water, in this view, is clearly a human right.

Nikhil Aziz is executive director of Grassroots International, a human rights and international development organization in Boston, MA that works on resource rights issues through grantmaking, education and advocacy. More information about GRI is available at http://www.grassrootsonline.org/.