By Peter Zelchenko

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

–Langston Hughes, “I, Too, Sing America ”

Lately grassroots and higher-level activity in food access planning has been growing. Americans aren’t leading healthy lives because they are overexposed to the standard menu of American mass culture. This has always ensured that food is a top target for reform, and the cost of food is always key.

The Past: Healthy Skepticism About Food Systems

Skepticism about food systems is not a new trend. Its roots go back to the Industrial Revolution. By the mid-nineteenth century discontent with company food store pricing and quality led garment workers to form the first food cooperatives in England. A century later, America ‘s social democratic movement of the 1930s brought us our own food co-ops. By the 1960s and 1970s, a back-to-the-land counterculture was accompanied by an urban organics movement that entered mainstream culture, the vestiges of which remain in the form of such products as granola, yogurt and tofu—food items virtually unheard of in America in the 1950s.

In the last twenty years, as urban areas have experienced new reinvestment, the middle class has seen a visible rekindling of interest in good quality food. Everywhere we are seeing green markets, local-foodshed organics and slow food, and in every American city there are people and institutions who have served as linkages from period to period, almost monastic devotees to tradition.

Present: Apples and Oranges

This latest period has raised awareness about the weak nature of healthy food access and food education for the poor. This has led to the identification of a “dietary divide,” yet another setback factor for the underprivileged, alongside inadequate access to education, housing, transportation and jobs, to name a few. This demographic is also considered highly vulnerable to suggestion by corporate marketing and without the time it takes to plan and prepare healthy meals.

Near Chicago ‘s infamous housing projects along the Dan Ryan Expressway, the only grocery store within walking distance has an entire aisle that is supposed to be for fresh fruits and vegetables, but the shelves contain not a single vegetable, only a few gallon jugs of a colored sugar water and citric acid mixture labeled “fruit juice.” When I asked recently why they have no apples or oranges, the owner replied, “They don’t sell.” Even in poor areas where there are apples and oranges, they are often overpriced and of low quality, according to Daniel Block, the Chicago State University demographer who has studied the West Side neighborhood of Austin.

A recent high-profile study in Chicago, done by the Metropolitan Chicago Information Center, showed food-access “deserts” in the poorest areas where there is crippling supermarket disinvestment. The study, bizarrely enough, went on to argue that the solution was more large, nationally run “hypermarkets.” Many planners would argue that such a solution is not in line with the new urbanist commitment to appropriate scale and locality, and to building a local economy. To put this all in perspective, around 1914 there were an estimated fifty neighborhood food stores per square mile, an average of one on almost every street corner. In the 1930s, there were twice as many per square mile. Today, in our so-called retail deserts, we count ourselves fortunate if there is even one.

The Future: Food Access Planning

On the recent recommendation of numerous academics and activists, who expressed concern about the fate of food access in Chicago, city officials convened a commission whose task it is to study these problems in greater depth. Although our vaunted Supermarket Task Force has already lost much of its steam, it may represent the first glimmer on the waves of American municipal governments taking some leadership role in solving problems of food access.

The most promising activity in Chicago has been on the ground. Activism and education are taking root in even the most at-risk neighborhoods. While strains of the 1960s “yogurt culture” have survived within America’s largely white middle class, groups coordinated by the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children (CLOCC), based at Children’s Memorial Hospital, have been taking the healthy food dialogue to inner-city families. CLOCC’s 1,000+ participant organizations are attempting to promote healthy eating in the trenches of Chicago by conveying positive messages about healthy food to children between three and five years old, directly through children’s schools and their parents. CLOCC is also promoting breastfeeding.

Inequities in Access

In my own contact with many poor African-American families, I have seen that food habits are based very little on nutritional value, much more on cost and ease of preparation. Still, grandparents understand the foodways of the old South and have great reverence for traditional foods like collard greens, legumes, humble cuts of pork and whole grains. These products can be had cheaply enough in most cities by the savvy shopper—yet they need to be prepared consistently enough to compete with a Burger King Whopper. But how exactly does one market such a food to grandkids, especially when such food, and much of the food of slaves and poor campesinos, is also often the most difficult to prepare? Greens, for example, take hours to stew tender, and a white activist, bent on promoting crunchy greens quick-chowed in canola oil, will never convert a black grandfather from his time-honored ways involving hours at the stove with pork fat, vinegar and brown sugar. His is still an enormously healthful product, and comforting to the weary soul.

Grandparents are still willing to buy and prepare traditional foods—and in many families they still do—but to find the products they need at a good value near their homes is becoming increasingly difficult. The problem is especially pronounced among African Americans, but Latinos also have less access and a great deal of child-oriented marketing to contend with. The point, however, should be clear: a significant number of families have some of the resources to help spark a cultural change.

The challenge standing in the way of healthy eating is not in what we serve on special occasions, but in what we serve every day. How can we bridge this dietary divide, merging the heart of food activists with the science of progressive planning towards praxis that is useful to those most at risk?

Very slight modifications to favorite recipes still result in products of almost identical flavor, with improved health benefits. Prepared greens, for example, already an ideal source for vitamins, iron and calcium, can be made with more canola oil and less pork fat. Delicious refried beans, an otherwise unbeatable source of fiber and protein, can be made with olive oil for everyday use, and abuelita can still use her manteca, the prized pork fat, for special occasions. Here is the key: moderation, through the will to re-elevate things to a special place.

The solution lies where the rubber meets the road—the food on the table—and the culture of acceptance and the discipline to consume it must come from family and school. From a marketing standpoint, this is doable, as groups like CLOCC are proving. Healthy products, from scratch ingredients or prepared, must be made readily available and priced as competitively as the always readily available unhealthy food. From a political-economic standpoint, this is also doable, but it must be supported through public policies.

Towards Supply Equity

My own involvement in this area has been twofold: first, to attempt to craft public policy that brings basic services like healthy, affordable supermarkets and restaurants to at-risk communities; secondly, to explore how homemade food, from basic ingredients, can again be made a self-righteous claim in respectable households.

Getting good supermarkets and restaurants into a neighborhood requires public pressure. Flying under the radar of many planners are the maverick independent supermarkets of 10,000 to 20,000 square feet, which evolved from the mom-and-pop corner stores of the early nineteenth century. These stores achieve economies of scale as members of wholesale buyers’ clubs, which provide house brands and competitive discounts for many staples. Several studies, including two of my own, have confirmed that these local independent stores are around 20 percent cheaper than the large stores run by national chains such as Safeway, Albertsons and Wal-Mart.

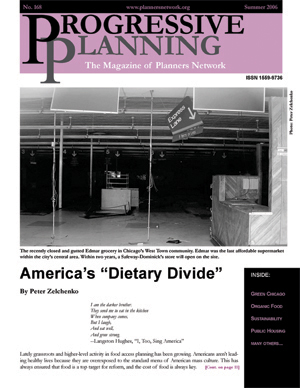

These local independents are owner operated and often family run, and they typically own their land. Accordingly, in the gentrifying ring around Chicago ‘s downtown core, they are dying off as retiring owners sell or lease their land—the land grab is less of a hassle than coaxing wayward children to take over the family business. Hypermarkets of 60,000 square feet and up (called “small” among national chain executives) have been supplanting these neighborhood stores, a trend supported by city development policy. In June, Edmar Groceries, the last affordable independent in Chicago ‘s 30 square-mile ring of gentrification around its central city, closed its doors. On its footprint will be a luxury Safeway Dominick’s store more than three times Edmar’s size, with a massive parking lot on the roof and a Starbucks inside. In an odd twist, Edmar’s owners, veterans of the grocery industry, will now become landlords to Safeway—burying their collective 150 years of experience underneath the foundation of a new building. Notwithstanding the fate of Edmar, there are still many of these smaller independents thriving just outside the ring of gentrification. This suggests that the business model of locally owned independents is still quite viable if only the cost of land can be dealt with.

I am working with Mrs. LaDonna Redmond of the Institute for Community and Resource Development to draft a plan to encourage right-sized grocery players to lease land in mixed-income areas and to enter blighted areas. In our plan, the city will consolidate some of its land holdings into larger parcels sited in places of greatest need, typically where the land values have gone too high or too low for investment. The parcels will be bound by covenants on their use, based on specific public need. The land will be entrusted to community development corporations (CDC) who will bind their leaseholders with further covenants, in exchange for leasing the land to them at below-market prices and city-financed tax incentives.

Preference will go to locally owned businesses and priority will be given to firms that commit to minority hiring. Healthy, affordable food access will be priorities for the city and the CDCs. Other essential businesses—pharmacies, laundromats, gas stations, even restaurants focused on serving healthy food—may be included in the plan. Density will be a key factor: to spur walkable competition, two of any type of institution, ideally, should be sited within a half-mile walk of any point in the city.

Picture a CDC leasing its 30,000 square-foot parcel to an independent grocer. The grocer commits to the city that it will sell 100 essential foodbasket items at or below the city’s average price. The grocer also commits to the CDC that it will always stock certain specialty items, such as our collard greens, at or below the city’s average price. It also promises to maintain a kitchen for free public cooking demonstrations sponsored by the CDC, restaurants and service agencies.

Cooking by Heart: Expelling the Market Toxins

My other effort has been to attempt to reconnect people with the experience of everyday food preparation. Americans are taught through commercial folklore to stick with prepared foods, and to leave the cooking and packaging to the experts. This phenomenon has crept into the culture so completely that now even water is bottled, and there is actual, palpable fear of drawing water from a tap. Don’t even think about buying a bag of flour, unless it is to slavishly follow a specific cookie recipe once a year. Try not to concern yourself with the flour’s true nature, and for heaven’s sake stay the hell away from yeast! This is the sad flip side of marketing prepared food.

My experience has been that when ingredients and processes are once again demystified, a new satisfaction will come from knowing about cooking. Again, the problem is connected with popular cultural perceptions. For example, whereas twenty years ago the cooking shows on public television, such as The Frugal Gourmet and others, patiently took the mystery out of simple, everyday food preparation, most programs on today’s Food Network seem to promote a culture of paralysis, where it is less taxing to sit on the couch and watch overhyped, high-class aficionados whip up fancy food than to get into the kitchen oneself. Even the ostensibly “do-it-yourself” types like Rachael Ray and Alton Brown seem to numb the senses unaccountably.

I prefer to show students that cooking can be very easy and uniquely satisfying once we are comfortable with just a few basic tools and emboldened by knowledge about the ingredients. We look at grains, legumes, vegetables and meats in an effort to understand just what they are and how and why they need to be prepared. We’ve learned that the tedious prescribed measuring typical in recipes is rarely absolute. Even things like baking powder, yeast and salt can usually be estimated. We’ve recaptured a “feel” for food preparation and taken pride in that knowledge, in addition to learning that hundreds of foods can be made easily from a few basic ingredients.

To connect this to food access, I have been quite sanctimonious about our right to get healthy ingredients at rock-bottom prices. Once a cook is not intimidated by cooking from scratch, once a cook understands the nature of, say, grains, he or she can tend to disregard three-quarters of the typical supermarket—the cookie, bread, pastry and cold cereal aisles—and for the most part monitor only the price of a few old-fashioned “dry goods” like flour, rice, corn meal and rolled oats. And, when they understand the food preparation process, they become experts when they do consider purchasing packaged food: Why must I buy these oatmeal cookies, encrypted in three layers of plastic, for $3.50 when I can make better ones this weekend with my children for 35 cents? From simple ingredients, and with increasing confidence, a hundred ideas and choices come into the cook’s head, and even cookbooks become almost irrelevant. Knowing the true secrets of cooking is a point of great pride for many people.

Healthy eating is a basic right as well as a responsibility. A subversive, practically militant, attitude about access to affordable, healthy food has periodically pervaded the counterculture. Translating this to America ‘s urban mainstream, particularly its most at-risk populations, is not easy, but it is what we as planners must do to bridge the “dietary divide.”

Adapted from a presentation entitled “Supermarket Gentrification” in the “Restoring the Urban Foodshed” conference session. Peter Zelchenko is a Chicago-based writer and columnist who is running for alderman of Chicago ‘s 43rd Ward in 2007. From 2000 to 2005, Peter led a grassroots campaign to stop the closing of the last affordable supermarket on Chicago ‘s Near West Side. Since then, he has persuaded officials to consider food access planning in Chicago. He can be reached at pete@printchicago.com or at http://zelchenko.com.

pete@zelchenko.com | http://ward43.blogspot.com | http://zelchenko.com