By Kelly Main

MacArthur Park is one of downtown Los Angeles’ largest and most historic public spaces. Located just a few miles west of City Hall and the corporate centers on Bunker Hill, the neighborhood in which the park is located is the poorest in Southern California and the densest west of Manhattan. The park is also at the center of a thriving Central American community, the residents of which began arriving during the political upheavals in El Salvador and Guatemala in the 1980s.

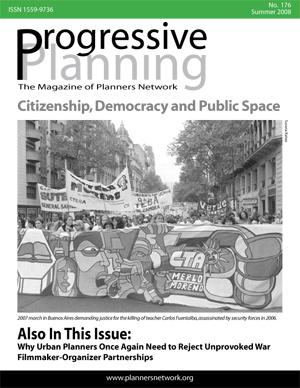

In March 2006, MacArthur Park was a focal point for one of the largest immigration rallies in the U.S. In response to anti-immigrant legislation being debated by the U.S. Congress, many of the marchers demanded full rights and legalization for immigrants. One year later, on May 1, 2007, a march commemorating the 2006 rally and reasserting immigrant rights was again held in downtown Los Angeles. The march ended in MacArthur Park, where participants, including children, as well as members of the press, were chased down by Los Angeles Police Department officers and struck with rubber bullets and batons. The police action, dubbed the “May Day Melee,” received national attention and sparked an investigation into the department’s behavior.

As a location for large-scale protests and rallies, local communities use MacArthur Park as a place to directly and visibly assert their rights, both political and spatial. In their everyday use of the park, community members also assert these rights, but in much less visible ways, at least to outsiders. Through daily activities such as soccer and vending, and through periodic celebrations, neighbors exercise their control of this community space. One of the most powerful assertions of local rights is through an unofficial soccer league, which serves more than 1,000 children and hosts activities every day in the park.

Local Histories

MacArthur Park, originally named Westlake Park, is located in the Westlake neighborhood, one of the first suburbs of Los Angeles. Spurred by the Pacific Electric streetcar system, the area began to develop in the late 1800s and quickly became one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the city. The park was designed in the tradition of the “pleasure grounds” of the time. A small homage to Central Park and Frederick Law Olmsted, the park was landscaped to reflect a “naturalistic” and rustic sensibility.

Westlake Park’s popularity increased and, by the 1920s, the park became a magnet for luxury hotels and apartments, such as the Park Plaza Hotel, still standing at the western edge of the park. Weekly concerts were featured in the park’s bandstand. A Victorian boathouse was built at the east end of the lake, and boating on the lake became a popular Los Angeles pastime.

The economic “decline” of the park is reported to have begun just after World War II with the middle-class exodus to the suburbs. Jewish immigrants began to move into the neighborhood (hence the regionally famous Langer’s delicatessen located in the corner of the park), followed by refugees fleeing wars in El Salvador and Guatemala in the 1980s.

Crime has been a serious problem in the surrounding neighborhood and the park. In 1994 there were 140 homicides in the Rampart Division, the police district that includes MacArthur Park. Police officers now patrol the park twenty-four hours a day, every day, and surveillance cameras have been installed. The New York Times (4/17/05) reported that by 2004, homicides in the Rampart District had dropped to 27 and, according to a more recent Los Angeles Times article (6/17/07), violent crimes in the area had dropped by 50 percent.

The Westlake Community and MacArthur Park Today

Today, the Westlake neighborhood is 78 percent Latino. Depending on how neighborhood boundaries are drawn, 65 to 70 percent of the area’s population is foreign-born, and fewer than half (46 percent) are citizens. Recently, local residents and business owners submitted a petition with 500 signatures to have the neighborhood surrounding the park designated as “Central American Town.”

Central American identity is just one of several identities associated with the area. The nearby Pico-Union district has become at least partially associated with Los Angeles’ burgeoning Mexican community hailing from the southern state of Oaxaca. In an attempt to link public spaces with the assertion of cultural and national identity, a Oaxacan group collected up to 2,000 signatures requesting that the City of Los Angeles rename nearby Normandie Park after former Mexican President Benito Juarez, a Zapotec Indian from the state of Oaxaca. MacArthur Park’s visitors reflect the identity of the larger neighborhood often represented in newspaper articles and other popular literature: immigrant, Latino and Central American and Mexican.

Playing Out Democracy: Soccer in MacArthur Park

One of the most prominent activities in MacArthur Park is soccer. The unofficial yet highly organized soccer league, serving over a thousand children, holds practices every weekday and games every weekend on two unofficial fields in the northern half of the park. According to Daniel Morales, the chief organizer of the soccer league, historic preservationists want to see the park return to its more historic role as a passive space with beautiful landscaping and without soccer fields. The preservationists argue that the park’s historic designation prevents any “new activities,” such as soccer, from being added to the park.

The soccer fields are located on what was once the lake bottom on the north side of the park. When the park was bisected by Wilshire Boulevard, the lake in the north half was drained, leaving a large grassy area. There are almost no trees directly adjacent to the fields, making for good views from the nearby grassy areas. The lack of trees means that viewers are exposed to the sun, and on summer days it can become quite warm on the field. Any grass in the field area has been worn away by use, exposing earth and resulting in a great deal of dust on windy days. The surface of the fields has been a major source of contention between the soccer league and forces opposing it. The league has asked for a proper surface, but according to the park manager and league organizer, those who would like to see the league gone want to see the dust taken care of and the area landscaped with grass. According to city officials, maintaining real grass for the fields, given their level of use, would be quite expensive. Thus, while still not officially sanctioning the soccer fields, the city approved funding in 2006 to put artificial turf over the fields.

In my research of the park, spanning a three-year period, it was clear that the soccer games are a major source of social interaction. On weekends, league games continue throughout the day. Just to the east of the two fields it is common to see games being played in small groups and many individuals and small groups working on their soccer skills. Throughout the year, 200 to 500 people watch the games at any given moment. The groups who gather around the fields are made up of family members who have children in the games as well as individuals and small groups standing on the sidelines. A grassy area that slopes up on the south side of the fields is a perfect place for a shaded but still excellent view. A great variety of social groupings occur there as well, including both men and women. Families greet other families with children on the same team. Men gather in small groups, watching the game and chatting about the players.

Park benches dot the circumference of the two unofficial fields. Daniel Morales brings portable goals and a tent, which he uses to operate the league. The tent is a hub of activity throughout the day, as coaches and players check in to find out about schedules and other organization matters. Particularly on weekends, it is quite common to see mothers or fathers approaching the tent to sign up their children, both girls and boys.

In the summer of 2006, the first Soccerfest was held at MacArthur Park. Sponsored by Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez, the event was, according to Speaker Nuñez’s staff, meant to reinforce the importance of soccer to the community and to the park at a time when the appropriateness of the soccer fields and the league was being debated, officially and unofficially, by city politicians. It was an assertion of both ethnic and political identity for the Latino population of the park and the neighborhood. Several Spanish-speaking television stations covered the event and one station sponsored it. Semi-professional teams played several exhibition games on the soccer fields, and the league played tournament games. Several politicians made presentations and awarded trophies to the winners. A grant was given to the league organizer to continue running the league. (Previously, the city had assisted the league, unofficially providing funds and staff from the park’s community center. Currently, this funding has been suspended.) Over the course of the day there were an estimated one thousand onlookers at the soccer fields.

The debate about the league continues among politicians, city staffers and the community, but not in any official public forum. The city is looking for other sites for the league. In what appears to be a nod to the significance of the league to the community and the lack of other locations for play, the city has allowed the league to continue using the park. In the meantime, over a thousand children play soccer in what Mr. Morales and many community members consider to be the best gang prevention program the neighborhood has. And despite claims that police surveillance has “cleaned up the park,” many park goers assert that the soccer league and the people it brings to the park are primarily responsible for the safer conditions.

Conclusions

It can be argued that many, if not most, local planning practitioners faced with how to address troubled public spaces or how to design new successful ones approach this challenge through urban design. More recently, some planning practitioners have become concerned with the social environment of public spaces and how social elements might affect sense of place—although it is arguable that most planners are primarily focused upon the activities that should be prohibited more than on the activities that might be encouraged or permitted.

My research suggests that local planning practice might benefit from several changes in approach to designing and regulating public spaces, particularly in urban settings. Giving greater consideration to the types of uses that are allowed or prohibited in public spaces might allow for more meaningful environments for users. Because the cultural communities that make up urban neighborhoods and their needs for public space can rapidly change, planners must be vigilant in their outreach to these communities. Community-based design efforts that concentrate upon physical design may be missing some of the most important elements of a democratically developed public space.

In MacArthur Park, the struggle is over local control of this public space to achieve a felt community need—the need for a safe place for children to participate in a culturally valued activity, in this case soccer. By affecting these small everyday negotiations over the use of public space, we planners, though we may not be conscious of it, can either help or harm. What may appear to be small, everyday negotiations over public space can actually reflect struggles for political and spatial justice. The annual rallies held in MacArthur Park reflect enormous national political struggles and take place there because of the everyday association with the park by the very groups most affected by the national struggle.

Kelly Main, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of planning at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo.