By Susana Kaiser

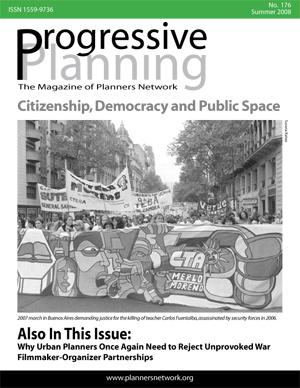

Since their irruption into the public sphere in 1977 in the midst of a military dictatorship, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (mothers of desaparecidos) pioneered the redefinition of the word public, which is at the core of the struggle for human rights in Argentina. By turning motherhood into a public activity, the group was crucial in resetting the boundaries of political spaces in Buenos Aires. By conquering and remapping urban territories, both physical and metaphorical, it shaped the style and the scope of human rights activism. Over the last three decades, and during distinct and changing political environments, the creative, strong and disruptive public presence of the group’s activists has played a key role in shaping public opinion and policies regarding memory, accountability, social justice and democratization. This public presence has been marked by numerous actions, including the Mothers’ communication strategies denouncing state terrorism and demanding accountability; escraches (demonstrations) organized by H.I.J.O.S (organization of children of desaparecidos formed in 1995), an innovative challenge to impunity and political amnesia; and street demonstrations (2001-2002) with tactics that included cacerolazos (banging saucepans) and piquetes(blocking of roads and streets) to demand the major restructuring of political institutions and the economy. The streets of Buenos Aires, thus, have become sites where denunciation, debate and negotiation take place.

Moreover, taking to the streets is aimed at conquering and remapping cultural, political and ideological zones. Since memory is encoded in places, the struggle for urban territories is also a means of enacting memory and writing history. Focusing on the relationship between physical space and event, I examine the symbolism of urban spaces in Buenos Aires as transformed and reconfigured by human rights activists—as spaces of changing and conflicting meaning.

Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo

When the Mothers first got together, their task was to communicate that their children were vanishing. Since their beginnings, they created a style aimed at shocking and galvanizing a paralyzed society. This style was marked by a powerful presence in public spaces and the establishment of the Plaza de Mayo (la Plaza) and the streets as their territory. Their assertive struggle for urban territories relied on marches, mobilizations and the use of symbols and symbolic spaces. The Mothers took over the square facing the government house, a landmark of Argentina’s political life, and marked this space with a new historical meaning. At the peak of the terror, their weekly marches became a reminder of the repression in this “liberated” territory.

The Mothers adopted street theater techniques, staging demonstrations on any occasion where witnesses could observe them and turning squares and streets into stages for these performances. If authorities asked one Mother for her ID, all the Mothers would hand in theirs; if one Mother was taken to the police station, dozens of Mothers would declare themselves jailed. When President Alfonsín cancelled a meeting, they staged a sit-in, turning the government house into an overnight encampment. They brought their children with them into the streets using large posters, each of a life-size silhouette symbolizing a desaparecido. These posters were mounted on walls throughout the city or on cardboard and, in the case of the latter, made to “march” in demonstrations. Giant photos were also used to decorate the Plaza. The Mothers were extremely creative in using graffiti to mark public territories. On occasions, they decorated the sites where military parades took place, painting street surfaces with their symbols, which resulted in images of soldiers marching over asphalt with painted accusations against them, such as boots interposed with white scarves (the Mothers’ symbol). Ironically, the streets as spaces for honoring the military turned into spaces for denouncing their crimes.

Hence, the Mothers’ activism has transformed and symbolically given new meaning to the urban landscape. Their street presence, their taking over of the Plaza, their marking of recuperated or liberated spaces and their visually compelling performances established guidelines that other activists would adapt.

H.I.J.O.S.

The acronym H.I.J.O.S. stands for Hijos por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio (Daughters and Sons for Identity and Justice against Forgetting and Silence).The group achieved notoriety for its escraches—campaigns of public condemnation aimed at exposing the identities of hundreds of torturers and assassins benefiting from impunity laws. Marchers invade the neighborhoods where torturers live carrying banners and chanting slogans such as “Alerta, Alerta, Alerta los vecinos, que al lado de su casa está viviendo un asesino” (Alert! Alert! Alert all neighbors, there’s an assassin living next door to you!). The group informs about atrocities committed by their targets, handing out fact sheets about them that include a photo, name, address, human rights violation(s) committed and current occupation. Demonstrations end in front of the torturers’ homes with a brief “ceremony”— speeches, street theater and music. Marchers then “mark” the location by spraying slogans on sidewalks and walls. Red paint—symbolizing blood—is usually splattered on building walls.

This symbolically powerful tactic of bringing back the past into the public sphere compels society to define its position toward human rights violations and campaigns for justice. H.I.J.O.S. developed its strategies within a political and cultural environment of legalized impunity. Hundreds of torturers and assassins were left free to roam public places and invited as guests on television talk shows. They had become “democratic” politicians and were even depicted as kind parents of children they appropriated after disappearing their biological parents. But only a few faces were known. Escraches tore off the shield of anonymity behind which hundreds of torturers hid. Through these acts, H.I.J.O.S., contested denial and ignorance by making people realize that those guilty of atrocities might be a kind neighbor or the father of a son or daughter’s friend.

The goal of the escraches was to curtail access to social spaces that torturers and assassins had gained. This constituted a metaphorical repossession of the streets, freeing them from the presence of criminals. Once the community has recognized them, criminals become restricted to the areas where they can circulate without being harassed and therefore become prisoners in their own homes. Escraches target military officers and their accomplices. Since the dictatorship introduced neoliberal economic policies in the 1990s, H.I.J.O.S. has organized escraches around those labeled “economic genocidal agents,” connecting state terrorism and more current economic situations. Thus, H.I.J.O.S. has made a point of exposing and shaming members of those sectors that condoned, collaborated with and benefited from the repression.

H.I.J.O.S. also developed follow-up “memory activities” to ensure that the momentum gained from the escrache does not fizzle out. One tactic is the “mobile escrache” in which activists revisit the residences of several criminals within a three-hour span, traveling from one to another by bike, car or chartered bus. Another activity is to return to the neighborhood following an escrache. The “post-escrache day” takes place in a public place where H.I.J.O.S. shows photos taken during the escrache, broadcasts from the site and organizes screenings and performances. The escrache thus becomes an ongoing event, with participation from the community, which reaffirms the boundaries of these re-conquered territories and broadens the territory of protest. No longer limited to the criminals’ residence, it includes parks or squares as new spaces to discuss and redefine the past.

Until the nullification of the impunity laws in 2003, and the consequent revitalized expectations for justice,H.I.J.O.S. should be credited with limiting the criminals’ social and spatial freedoms. The group’s escraches trapped torturers and assassins by building metaphorical jails in neighborhoods throughout Argentina.

Twenty-First Century: The New Escraches, Piquetes and Cacerolazos

At the turn of this century, the streets of Buenos Aires became the site ofmassive demonstrations triggered by a new political crisis. Citizens made headlines with theircacerolazos, taking to the streets armored with saucepans that they loudly banged while calling for the ousting of those in office: “¡Que se vayan todos y que no quede ni uno solo!” (Throw them all out!). Such was the anger and frustration with the political class. During the turmoil of December 2001, though demonstrators were brutally repressed, the president was forced to resign.

Those were times characterized by an array of struggles for basic human rights. People organized to ask for jobs, food and shelter, and to protest authorities’ moratorium on bank savings withdrawals. Various social actors developed strategies to demand democratization. The caceroleros were accompanied by the piqueteros, who blocked streets and points of access to the city. Demonstrators chanted a slogan conveying the concept of a unified coalition: “Piquete y cacerola: la lucha es una sola” (Blocking and saucepan: there’s only one struggle). Cacerolazos and piquetes, strategies involving the temporary ownership of territories with the purpose of confronting the enemy, be it a corrupt government or unemployment, became other means to transform urban spaces.

The movement of ahorristas (holders of frozen savings deposits) adopted various tactics for occupying public spaces. For instance, people unable to go on vacation brought their chairs and coolers and sat outside the bank, as the alternative to picnics at the beach. While these protests were localized in the financial district, the ahorristas also borrowed from the piqueteros, blocking streets in other areas of the city and expanding their territory of disruption.

Neighborhood assemblies brought together large sectors of the community to analyze the crisis and make political decisions. Citizens discussed issues ranging from Argentina’s foreign debt to unemployment, including the high fees of privatized public services. During 2002, the gatherings of the massive inter-neighborhood association in Parque Centenario, located in the geographic center of Buenos Aires, turned the park into the “legislative chamber” for an experiment in grassroots democracy.

A new breed of escrache, modeled after that of the H.I.J.O.S., was adopted by other organizations. These escraches have been directed against politicians, businessmen or anyone in a position of power considered responsible for a crisis. The target can be a former minister, the director of a bank or someone blamed for layoffs. Some escracheshave condemned official economic policies, as those directed at delegations of the International Monetary Fund upon their arrival at the airport. There have also beenescraches against the media in which those shunned by it reacted against it for ignoring their role as key protagonists. The slogans painted on walls and chanted during theseescraches summarized the perception that the media distort what happens in the streets, as illustrated by the blunt statement: “Nos mean y los medios dicen que llueve”(They urinate on us and the media say that it’s raining).

In Summary

Although the political environment is constantly changing, a strong street presence is the quintessential characteristic of human rights activism in Argentina. We talk of street demands, streets as spaces for deliberation, streets as arenas to denounce injustices and administer popular justice. Both the Mothers and H.I.J.O.S. defined a new style of demonstration, part of a project to reshape the uses of public places of the city. Over the years, activists have been learning from different struggles and techniques, borrowing, adapting and innovating. We can identify common traits, including the performative connotations of these demonstrations, often highlighted by the presence of musicians or actors. In a bustling metropolis, activists need to compete for the public’s attention.

The struggle for urban territories still takes place in a city rich in locations where people can demonstrate, from wide avenues to squares, such as the Plaza de Mayo, a site that is a heritage from the colonial days when the “plaza mayor” was the town’s heart. But we cannot ignore an ongoing process of curtailment and privatization of the public space. The fencing off of squares, increasingly common, limits the hours that citizens can use them, and new malls and shopping centers shield people from street protests.

There are significant differences between the dictatorship and civilian rule. In response to the dictatorship’s discouragement of criticism and its promotion of limitations on justice, the activists’ loud street chants act as a challenge—to what can be achieved, to what can be dreamt. When night falls, legions of cartoneros (those collecting paper and cardboard) start their nightly ritual of digging into the rubbish. Entire families turn the streets into their workspace, a large recycling plant. They hope to survive by collecting, classifying and selling what others discard. It is hard to think of another situation that symbolizes so well the cycle of exclusion. Demonstrators keep roaming the streets to expose their conditions and fight for their rights. The urban spaces of Buenos Aires continue to be re-signified by ongoing protests. Activists seem convinced that the streets continue to be one of most relevant political spaces, the logical and appropriate setting to exercise their political life.

Susana Kaiser (kaisers@usfca.edu) is an associate professor in the Department of Media Studies and the Latin American Studies Program at the University of San Francisco.