By Jason Neville and Clara Irazábal

Weeks have turned to months and months to years as New Orleanians—both those living in the city and those yet to return—have waited in vain for leadership and resources from local, state and federal sources. In the face of such neglect, and united with a determination to rebuild their lives and communities, many residents and grassroots organizations have begun planning for their devastated communities on their own, far too committed to restoring their city and neighborhoods to continue to wait for “help from above.” The unprecedented scale of autonomous neighborhood-based planning activities are not simply taking place in absence of official planning, but tocounteract the inept and non-participatory planning processes that have plagued post-Katrina New Orleans.

Attendees at this year’s Planners Network conference in New Orleans were intimately exposed to these grassroots phenomena through community-based panels and workshops. While most planners that have come to New Orleans have typically spent their time promoting their own ideas for the city’s recovery, the conference attendees embarked on a kind of “listening tour” in this increasingly plan-weary town. Whether touring the city’s commercial recovery areas by bike, helping gut a new community center outside the St. Bernard housing project or visiting a community-based urban design project hosted by residents, Planners Network members got to see and hear about the community-based recovery efforts led by residents and grassroots leaders. In doing so, conference attendees were able to observe firsthand the prospects—and limits—of this grassroots planning surge.

As Lauren Andersen, an organizer with the non-profit Neighborhood Housing Services, told us in an August 2006 interview, “What’s happening in New Orleans right now is really almost revolutionary.” Another non-profit housing leader working in Central City, Paul Baricos, told us that the surge of autonomous neighborhood planning was

a great sign for participatory planning in New Orleans. There are scores of these [autonomous neighborhood-based] meetings taking place across the city to do ‘planning.’ It’s a truly indigenous phenomenon. Much of it was a reaction to the Bring New Orleans Back Commission’s mandate that neighborhoods prove their own ‘viability,’ but it would’ve happened anyway. These groups all came together through the neighborhoods themselves. The City Planning Commission has had zero role. And the mayor’s Bring New Orleans Back Commissionsaid that they’d provide assistance, but it has yet to materialize.

One of the best examples of this grassroots planning has been in the Broadmoor neighborhood—an ethnically and economically diverse community located on some of the lowest elevations in the city, and one of the several neighborhoods that the Bring New Orleans Back Commission recommended be reverted to green space. According to the Times-Picayune, the commission’s proposal “electrified a diverse group of homeowners who reached out to each other, determined to save their community” and “turned their once sleepy Broadmoor Improvement Association into a grassroots planning powerhouse.” This was no weekend charette; according to the local newspaper, the neighborhood “conducted resident surveys, shared information on contractors, established a system of block captains and began talking about how their neighborhood should be fixed.”

In another potent example, and one which was part of a conference community-based workshop, the Vietnamese community of New Orleans East developed a community plan that included resident surveys and proposals for an improved business district, linear parks along canals and a community housing development adjacent to the prominent Mary Queen of Vietnam Catholic Church. The report issued, complete with plan and section view drawings of the proposed new districts, was developed solely by the community with no support or coordination from the local, state or federal governments. Reverend Vien Ngyuen, the leader of the church, was quoted in theTimes-Picayune: “We were never invited to the table [to plan for our community]. . .we have the right to be part of the community-driven process.” In addition to becoming a relief center and a community planning entity, the church also became “one of the community’s key political voices in opposing a new 88-acre landfill the city wants to open in eastern New Orleans.”

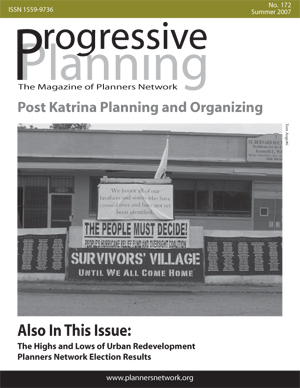

Radical political activists have played a prominent role in the grassroots recovery efforts, working to ensure the right of return for working-class African-American residents still trying to get home. In January 2007, a group of housing activists and former residents illegally entered the St. Bernard housing project—closed and gated by HUD since Katrina—to clean the mildly damaged apartments and restore them as decent affordable housing. HUD officials stood by helplessly as dozens of residents stormed the gates and began gutting and painting the apartments. During the conference, some attendees assisted with these efforts by helping to clean and gut a new community center across from the condemned housing project.

- A contingent of community leaders from the New Orleans Survivor Council recently traveled to Venezuela to learn from that country’s consejos comunales(communal councils), part of the Venezuelan government’s national planning strategy to decentralize, democratize and fund planning efforts at the neighborhood level. They also solicited community organizers and funding from the Venezuelan government for recovery efforts in New Orleans, denouncing the abandonment of their own governments in the U.S.

The tendency for informal, collective, transformative action in New Orleans, particularly in working-class African-American neighborhoods, predates the post-disaster recovery efforts. The extraordinary “second-line parades” that often erupt in the working-class African-American neighborhoods are hosted by “social aid” and “pleasure” clubs with fantastic names like the Treme Sidewalk Steppers, the Double Nine High Steppers, The Moneywasters and the Happy House Social and Pleasure Club. These organizations began as neighborhood-based mutual aid societies that pooled resources for insurance, funeral arrangements, direct financial assistance and other forms of socio-economic support for needy members who lacked access to formal institutions during the discriminatory era of Jim Crow New Orleans.

The autonomous, informal mutual aid societies and their symbiotic street celebration extensions reflect a strong inclination toward collective action, an auspicious demonstration of the possibilities of grassroots celebratory democracy in New Orleans. One 7th Ward-based anthropologist, Helen Regis, working with Rachel Breulin, writes that most of the participants in these organizations “are not ‘owners’ of homes, real estate or large public businesses. Yet through the transformative experiences of the parade, they become owners of the streets … experiencing a transcendent power in this collective celebration [and] continuing to speak to the contemporary struggles of the city’s majority black and working-class population.”

Comparison Cases from the U.S. and Beyond

Communities in both the U.S. and the so-called developing world have used “openings” in the political order that often arise after disasters to autonomously transform their neighborhoods and cities. In the U.S., some important reforms have been advanced during disaster recovery efforts. Like for Katrina, federal response was also slow in arriving for Hurricane Andrew and consequently, community organizations in Florida played an important role in the immediate disaster recovery efforts, feeding, housing and counseling victims. In addition, some lasting policy reforms were initiated after Andrew, such as the creation of state-backed insurance programs to provide coverage after many major insurers abandoned coastal Florida and new building codes to make homes more “hurricane-proof.” After the 1994 Northridge earthquake in Los Angeles, community-based housing organizations were able to use the post-disaster context to expedite the development of almost 150 new housing units, all of which where designed to meet the needs of the larger (yet neglected) Latino households that dominate the area.

Yet the grassroots post-disaster planning in the “developing world” has particular salience because of the capacity for more radical transformation that emerges in the face of nearly total state abandonment, as is the case in New Orleans. Indeed, as Faranak Miraftab suggests, transformative planning may be more possible in developing world contexts because of the minimal attention to these communities paid by the state. For instance, following two back-to-back earthquakes in Mexico City in 1985 that killed 5,000 people and left 2 million homeless, residents initiated a disaster recovery and planning effort without any assistance or guidance from the government. This included delivering housing and medical services while maintaining a strong vigilance for social justice and equality, directly contradicting the government’s top-down approach. Most important, writes Diane Davis in her account of this grassroots planning effort, is that the residents’ “self-organization around recovery efforts in turn produced lasting changes in the politics of the city [and] served as a central political force in subsequent struggles for the democratic reform of the city government.”

Additionally, the government’s preoccupation with restoring the “macroeconomic standing” of the city and country—i.e., rebuilding high-profile buildings and institutions and accepting World Bank loans for long-term infrastructure projects, rather than addressing immediate humanitarian needs—called the entire logic of Mexico’s political economy into question among ordinary residents. This suggests that disasters such as Hurricane Katrina can also trigger a broadening of political consciousness beyond material concerns, exposing contradictions and failures in the overall political economy.

Another example of transformative post-disaster planning followed the 1999 earthquake measuring 7.4 in magnitude in Golcuk, Turkey. The quake damaged almost 250,000 residential and commercial units and killed 17,480 people. Meager recovery assistance and planning by the government shattered the people’s trust in the centralized and elite Turkish government, which had fostered a weak civil society. Facing the deep incapacity of the government, “civil society rose to fill its void by playing an active role in the quake zone, gaining broader trust and respect” that was likened to a great “awakening” of civil society. Self-organized groups worked to not only provide immediate search and rescue efforts, but also to begin the process of delivering longer-term services, such as medical, housing, food, clothing and financial aid. While some members of the government were appreciative of these groups’ work, the reaction from the state was one of skepticism and at times open hostility. Sensing the potential for larger political agitation to emerge from such organized and democratic institution-building, the government attempted to halt some activities by imposing strict measures on their operations, encouraging international aid to be channeled through state-controlled institutions and threatening lawsuits. Reflecting on this experience, Emel Ganapati asserts that disasters can act as catalysts for rapid development and the unleashing of dormant social capital.

New Orleans as Caribbean Capital: A New Context for Transformative Planning

New Orleans is often (and rightly) criticized for its parochialism, insularity and unwillingness to accept outside help, even when it would be in the city’s best interest. What Katrina has demonstrated, however, is that while many New Orleanians think of the city as a kind of non-American “Banana Republic,” so do the national and state governments—in a far more damaging way. Planners can see this disownment of New Orleans by the state as an opportunity to engage in directly transformative action.

The neighborhood solidarities, celebratory and supportive social aid clubs, instincts for self-help, deep suspicions of state interventions and the overall socio-cultural resilience of residents are all deeply rooted in the city’s Afro-Caribbean essence, auspicious indicators of the potential for broader democratic transformations during this historic city-making moment. The recovery examples above from “third world” cities speak to the transformative potential of grassroots planning efforts in New Orleans. If conceived of as a city in the Caribbean Rim, rather than as an antiquated and backwards American city, new possibilities emerge that allow us to imagine creative and progressive ways to rebuild and transform New Orleans into a more democratic and equitable city. Planners must pay critical attention to facilitating the return of New Orleans residents who want to return and capitalizing on the vibrant social capital of New Orleans’ neighborhoods for that process.

Planners should consider the resilient social networks and working-class solidarities of the city as unique strengths upon which to build a community-based recovery strategy that formalizes a participatory planning process without bureaucratically bludgeoning the democratic instincts of residents. Progressive planners can work to incorporate new planning tools, such as community-based design and participatory budgeting, to democratize the physical and institutional structures of the city. Planners can also help to resolve the biggest question of all—where (and where not) to rebuild—by helping to reestablish neighborhoods and their critical social networks on “drier” areas of the city, protecting those communities from future disasters without sacrificing the vibrant cultures that have sustained them for generations or marginalizing any particular class of residents from the recovery.

To restore social networks and facilitate more transformative planning cultures in the city, the remaining residents who are still living in a nationwide diaspora must be allowed, encouraged and directly assisted to return immediately. Planners must play a dual role, that of professionals working from within the political system as well as that of activists organizing from outside of it. We must acknowledge the inherently political nature of planning and the racist and classist contexts in which it is situated, agitate for structural change and ally ourselves with the marginalized communities of New Orleans, taking leadership from them and building community capacity to transform the system from the neighborhoods up.

Jason Neville is from New Orleans, moved to Los Angeles one month before Katrina and is now a planner at the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency. Clara Irazábal is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California. This article draws on half a dozen return trips to New Orleans since the flooding as well as experiences at the PN 2007 Conference, and is based upon the forthcoming article “Neighborhoods in the Lead: Grassroots Planning for Social Transformation in Post-Katrina New Orleans?” in Planning Practice and Research (abbreviated with permission)